Noah’s Navigator is available in the museum gift shop 1-4 p.m. Tuesday thru Saturday.

Thank you Noah’s Navigator sponsors.

Noah’s Navigator

Solve the puzzles ~ Find the signs ~ Success

Noah’s Navigator is a puzzle book and scavenger hunt in one. Solve the puzzles to identify 10 locations in West Hartford. At each location, look for a Noah’s Navigator sign so that you will know you found it!

Noah’s Navigator is fun for kids and adults and is available in the museum gift shop for $20 Tuesdays through Saturdays , 1-4 p.m. at 227 S. Main Street, West Hartford, CT.

Looking for a unique group activity? Purchase 10 or more Noah’s Navigator packets and receive 10% of each.

Noah’s Navigator Notes

***Spoiler Alert***

You may want to complete your scavenger hunt before reading further. The information below will give clues to scavenger hunt locations.

There is so much more to learn about the history of West Hartford! You will notice notes in your Noah’s Navigator booklet that lead you to this website to learn more about many of the locations you found.

Location 1 – It is easy to walk past this place with hidden history.

This little stone monument has been here for over 200 years! When first installed, it helped travelers know that there were only 4 miles to go to reach the State House in Hartford. (It is now called the Old State House.) You may be able to make out the engraving which reads “H IV M.” The “H” for Hartford, “IV” is the number 4 in Roman numerals, and “M” for miles. This might make you wonder what other hidden history you walk past each day?

Location 2 – Revolutionary War veteran Prut wasn’t added until 2019.

You’ve discovered this item at a monument that commemorates the sacrifice made by many people, including some from Noah’s time. Noah was studying at Yale during the Revolutionary War. His life and studies were greatly impacted by the unrest and war itself. Noah and his family, like many West Division residents, were proud patriots. Many men from Town joined the fight for the nation’s independence – most, of their own free will, but not all of them. Prut was an African-American man who was enslaved by the Whitman family. It is believed that Prut may have been sent to war in place of the man who enslaved him. Imagine fighting for the ideals of liberty when you yourself are not free? Prut paid the ultimate sacrifice – he lost his life at the Battle of Fort Ticonderoga. Thanks to the efforts of the Witness Stones West Hartford project and a group of students from Renbrook School, Prut’s name was added in May 2020 to the Revolutionary War monument. Prut is believed to be the first African American to be honored on the memorial.

(In this picture from the Hartford Courant, Marc Boucher, stone carver and engraver for Independent Stone in Stafford Springs, puts the finishing touches on Prut’s name on the memorial. You can read the full Hartford Courant article on the addition of Prut to the war memorial here.)

(In this picture from the Hartford Courant, Marc Boucher, stone carver and engraver for Independent Stone in Stafford Springs, puts the finishing touches on Prut’s name on the memorial. You can read the full Hartford Courant article on the addition of Prut to the war memorial here.)

Location 3 – New stones are added to this old location each year.

While slavery is not something typically associated with New England towns, in fact some of the town’s most prominent early families – the Sedgwicks, Goodmans, Coltons, Hookers, Hosmers, and others – were slaveowners. Today you can see roads and buildings with these family names, but the history of the men and woman they enslaved in the 18th century had been largely forgotten until the Witness Stones West Hartford project began uncovering their stories.

The Witness Stones project was brought to West Hartford in the spring of 2018, when 42 students began researching enslaved men George and Jude, and studying more about Bristow, the namesake of West Hartford’s Bristow Middle School. Since then, thousands of students (young and old) have participated in researching and learning about dozens of people enslaved in West Hartford in the 18th century with the guidance of project directors Dr. Tracey Wilson, Elizabeth Devine, and Denise deMello. You can learn more about the Witness Stones West Hartford project here.

The Witness Stones project was brought to West Hartford in the spring of 2018, when 42 students began researching enslaved men George and Jude, and studying more about Bristow, the namesake of West Hartford’s Bristow Middle School. Since then, thousands of students (young and old) have participated in researching and learning about dozens of people enslaved in West Hartford in the 18th century with the guidance of project directors Dr. Tracey Wilson, Elizabeth Devine, and Denise deMello. You can learn more about the Witness Stones West Hartford project here.

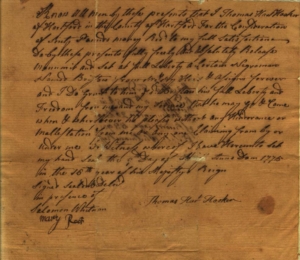

Until 2018, Bristow was the only African American with a headstone in Old Center Cemetery. Bristow (sometimes called Bristol) was enslaved by Thomas Hart Hooker and purchased his freedom in 1775. His manumission paper, left, is in the collection of the West Hartford Historical Society. As new people are researched by the Witness Stones West Hartford project, actual stones – the witness stones – are placed near Bristow’s gravestone. There are over 35 stones for you to discover!

Location 4 – In 2020, the name of this location changed.

The land used as the West Hartford Town Green was donated to the First Church of West Hartford by Timothy Goodman in 1747. During the Revolutionary War, local militia men trained on the green, preparing to defend their rights. Over the last 250 years, many important events and celebrations have been held in this historical spot, originally known as Goodman Green.

Thanks to the efforts of the Witness Stones West Hartford Project, we learned that Timothy Goodman was a slave owner who enslaved at least three men including a man named George. (You can find a plaque honoring George as Location 3.) Timothy Goodman’s wealth and ability to donate land came, in part, from enslaved people. Given this rediscovered history, the First Church West Hartford, the Town of West Hartford, Concerned Parents of Color West Hartford, and some of Timothy Goodman’s descendants met to discuss what to do about the green. On November 29, 2020, the Congregational Church voted to change the name of the location from Goodman Green to Unity Green.

Location 8 – Other work by this sculptor celebrates Indigenous heritage.

This statue of Noah was sculpted in the early 1940s by Korczak Ziolkowski. Up to 1,000 people at a time would gather in the summer of 1941 to watch Korzcak Ziolkowski sculpt the giant block of marble originally placed near the corner of South Main Street and Memorial Road. The artist’s defiance of the Blue Laws (he continued his work on Sundays) and his tendency to sculpt shirtless upset local sensibilities at the time.

This statue of Noah was sculpted in the early 1940s by Korczak Ziolkowski. Up to 1,000 people at a time would gather in the summer of 1941 to watch Korzcak Ziolkowski sculpt the giant block of marble originally placed near the corner of South Main Street and Memorial Road. The artist’s defiance of the Blue Laws (he continued his work on Sundays) and his tendency to sculpt shirtless upset local sensibilities at the time.

Ziolkowski was born in 1908 in Boston to Polish parents. Although he never had formal art training, he went on to do great things. Ziolkowski won first prize at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, worked on Mount Rushmore, and in 1948 was chosen by Chief Henry Standing Bear and fellow Lakota leaders to create the Crazy Horse Memorial in South Dakota. Learn more about this monumental undertaking here.