West Hartford History

Introduction

In many ways, the history of West Hartford epitomizes the evolution of numerous towns across America. Founded predominantly by Protestants in the 1700s out of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the small town remained rooted in agriculture into the early 1900s when first the well-to-do from Hartford and later the largely white middle class moved away from city life to create one of the state capital’s thriving suburbs.

Today, West Hartford has a population of approximately 61,000 residents and covers 22.2 square miles. To the north it borders Bloomfield, to the east Hartford, to the south Newington, and to the west Farmington and Avon. Far from the once homogenous mix of residents, the 2000 census recorded 66 different languages and dialects being spoken in the public schools. These include Punjabi, Cantonese, Arabic and Icelandic. There are now over 30 different places of worship in the community.

In recent decades, with the building of West Farms Mall, Blue Back Square and other developments, the town has taken on an appearance and population of an emerging city, but the culture of a small town is largely retained. West Hartford’s history is very much like many towns across the United States – it has continued to be altered and shaped by trends in industrialization, transportation, and the mass migration from urban centers to rural (soon to be urban) landscapes.

A Community Develops

According to archeological evidence, the Wampanoag Native Americans had used West Hartford as one of their winter camps. Fishing and hunting along the Connecticut River, the area of West Hartford offered the Wampanoag a refuge from the cold winter wind and the river’s spring flooding. This quickly changed once European settlers moved in and claimed the land for themselves. In 1636 Reverend Thomas Hooker led a group of followers from what is now Cambridge, Massachusetts to the “Great River” and established the Hartford Colony. As the Colony grew, additional land was needed. In 1672 the Proprietors of Hartford ordered that a Division be created to the West. A total of “72 Long Lots” were laid out between today’s Quaker Lane in the East and Mountain Road in the West. The northern boundary was Bloomfield and to the South was present day New Britain Avenue (The Western boundary was extended in 1830 to include part of Farmington). In the 1670s the area was referred to as the “West Division” of Hartford. This remained the official name until 1806 when Connecticut’s General Assembly started referring to it as “the Society of West Hartford.”

It is believed that the first homesteader to West Hartford was Stephen Hosmer whose father was in Hooker’s first group of Hartford settlers and who later owned 300 acres just north of the present Center.

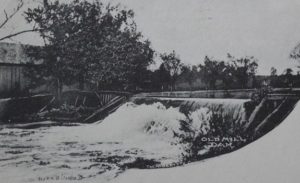

The site of Hosmer’s Mill

In 1679, Stephen Hosmer’s father sent him to establish a sawmill on the property. Young Hosmer would go back to live in Hartford, but in his 1693 estate inventory, 310 acres in West Hartford along with a house and a sawmill are listed. For nearly a century the property would be handed down through the family. Evidence still remains of the Town’s first industry. Stephen Hosmer’s mill pond and dam can still be found on the Westside of North Main Street.

By the time of the American Revolution, the once rugged wilderness had been largely deforested and an agricultural based community had developed with a population of 1,000 residents. At its core was the parish meeting house.

Congregational Church, 1st Meeting House 1712

The first Congregational meeting house was built around 1712 at what is now the northwest corner of Main Street and Farmington Avenue. As the focus of early religious, political, and social life, the meeting house helped to provide this area with a name, a title that it still holds today – “The Center.”

The Coming of Industry

In his history of West Hartford, the respected local historian Nelson Burr noted that Reverend Nathanial Hooker’s 1767 census documented a predominately agricultural community. The 150 households shared 1,920 acres of plow land, 2,560 of meadow and 3,200 acres of pasture. With an estimated population of 1,000 the 3,000 sheep that the census noted outnumbered people by 3 to 1. In addition to livestock, the Town had a thriving distillery business that relied on local crops of grain and apples. While many of the farms were small family run operations, several were more affluent. Evidence in the Hartford Courant and in the 1790s census show that some of the more prosperous households relied on laborers and slaves for fieldwork and domestic help. One such residence was that of Thomas and Sarah Hooker which still stands on New Britain Avenue. Evidence shows that they had several slaves to run their farm including Bristow who bought his freedom in 1775 and became a local agricultural expert.

Early on, grist, saw, and carding mills along with blacksmith shops, tanneries, and general stores emerged around the community to support and help drive agriculture. One of the first major industries to arise centered on the pottery and brick works. Extending from Hartford to Berlin is a sizable deposit of fine clay. In 1770, Ebenezer Faxon came from Massachusetts and settled in what would become the Elmwood section of West Hartford. There he established a pottery on South Road (what is today New Britain Avenue) which took advantage of the local geological landscape.

Goodwin Pottery

It was Seth Goodwin, however, who helped to establish a pottery dynasty. Goodwin started his pottery works around 1798. For over a hundred years, the Goodwin name would be associated with West Hartford pottery.

Producing utilitarian items such as jugs for the gin manufactured in local distilleries, to terra cotta designs and fine china, the Goodwin Company employed up to 75 people in its heyday. The Goodwin Brothers Pottery Company (as it came to be known) burned for the third time in 1908 and never recovered.

In 1879 Edwin Arnold established the Trout Brook Ice & Feed Company. Ice from Trout Brook, a stream that runs through the middle of West Hartford, was harvested in the winter, sawn into blocks, and placed into a series of ice houses through an escalator system. Insulated in sawdust, the blocks of ice were used as refrigeration locally and shipped as far away as New York City.

By the late 19th century, the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad ran through part of Elmwood in the southeast corner of town. A variety of companies cropped up in this area including Whitlock Coil Pipe Company in 1891, and later Royal Typewriter, Wiremold, Abbot Ball, Colt’s Manufacturing and Uncle Bill’s Silver Grippers (producer of tweezers).The largest of West Hartford manufacturers was Pratt & Whitney. In 1940 it built a plant on 20 acres and at the height of World War II it employed over 7,000 people.

In recent years, many of the old manufacturing companies have gone out of business or moved away. However, in Elmwood and in several other sections of West Hartford several of these businesses remain.

Independence Found

Following the American Revolution, residents of the West Division of Hartford began looking for their own political independence. In 1792 a committee of residents was appointed to ask permission from Hartford to secede – this was denied. Five years later they petitioned again and again were denied.

In the spring of 1854, the Connecticut General Assembly was meeting in New Haven (co-capitol with Hartford at the time). Most likely taking advantage of the distance from Hartford, a petition dated March 21 was delivered to the General Assembly by delegates from West Hartford. Signed by 153 residents, the petition claimed that residences were “subjected to many inconveniences on account of their present connection with the town and city of Hartford and that their convenience and prosperity would be essentially promoted by being set off as a separate town.” On April 26, about 100 residents from West Hartford presented their own case against secession. After review and an opportunity for Hartford to make an argument for keeping West Hartford, the General Assembly voted on May 3 for West Hartford’s independence.

The 1854 vote was not however the end of the debate. In 1895 wealthy residents from the “East Side” of West Hartford petitioned Hartford for annexation. Their call was rebuffed by other West Hartford residents. Then in 1923 and 1924 Hartford wanted to annex West Hartford back so that it could achieve a “Greater Hartford Plan.” Town residents rallied in opposition and the plan was defeated by a vote of 2,100 to 613.

Over a hundred and fifty years since it gained its independence, West Hartford still celebrates its distinctive community spirit. In 2004, residents came out in the thousands to commemorate the town’s sesquicentennial through parades, exhibits, programs, and festivals.

Pastimes

William Hall

In 1930, at the age of 85 William H. Hall, an educator and amateur historian reflected on how West Hartford residents spent their leisure time while he was growing up in the 19th century. He noted that “in the good old days” people spent their time at husking bees, taking long sleigh rides, joining the local singing society, church gatherings, exploring the natural landscape on picnics, taking adventurous journeys to distant parts of Connecticut and beyond, and enjoying parties with family and friends. While some of these diversions have changed, others remain just as relevant today as they were in the 1930s or in the 1860s when Hall was growing up.

Taverns in the 18th and 19th century were common places for public assembly. Many locals and travelers frequented them for entertainment, camaraderie, political discourse, business meetings, food and drink and—as rumored about one tavern in the Center – sometimes illicit activities. Between 1775 and 1820 the Hartford Courant mentions at least eight taverns in town. One of the most prominent of these was Aaron Goodman’s Tavern in the area of today’s Bishop’s corner (situated along the Old Albany Stagecoach Road). In 1820 it became West Hartford’s first Post Office and was the site for many formal and informal gatherings.

By the mid to late 19th century, a few West Hartford residents looked at entertainment differently and sought to develop local tourism. In 1873 Charter Oak Park was established in the Elmwood section of town. Pulling thousands of people each year, primarily from Hartford, the track was part of the Grand Circuit of harness racing until 1925 when it went out of business due to the establishment of Connecticut’s anti-betting laws. Connected with the race track was Luna Park. Dubbed “West Hartford’s Coney Island”, the park offered people from Hartford and the surrounding communities diversions including a midway, rides, and a variety of entertaining acts. In 1926, Charter Oak and Luna Park became the Connecticut State Fair grounds. Unable to compete with the New England Exposition, the site fell into disrepair and in 1940 became the location for Pratt and Whitney’s new plant. While the landscape has changed significantly from that of Hall’s childhood, West Hartford has thoughtfully approached its outside recreation. The quality of leisure life is high, with 28 town parks and open areas covering 1,200 acres, six reservoirs surrounded by walking and hiking trails, and four golf courses – two of them public. Westmoor Park in particular offers a range of programs for children and adults that allow them to enjoy nature and explore West Hartford’s farming past.

An American Story: The Making of a Modern Suburb

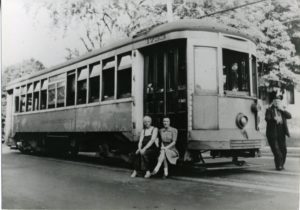

It is transportation that has had the biggest impact on West Hartford and its evolution from sleepy crossroads to modern suburb. In the late 18th and early 19th century three turnpikes ran through West Hartford. Around these roads, taverns, blacksmith and wheelwright shops, general stores and many other places of businesses sprang up. Early maps provide a sense of how important these byways were in the development of commerce and industry. Then came the trolleys – starting in 1845, Fred Brace began running a horse-drawn omnibus from his home on the corner of Farmington Avenue and Dale Street into downtown Hartford. Even more significant were the horse-drawn trolley lines and later electric trolleys that in 1889 began to weave their way from the inner city of Hartford to the countryside of West Hartford. The trolleys opened up a land that had been inaccessible to many. In 1895, Wood, Harmon and Company created one of the town’s first subdivisions with Buena Vista – or as they promoted it “Hartford’s new and handsome suburb.” Their literature highlighted “splendid suburban electric car service” and its proximity to Reservoir No. 1. Other developments followed including “Elmhurst” in Elmwood (1901), and Sunset Farm (1917). One of the most exclusive of these early developments was West Hill. Located on the former estate of Cornelius J. Vanderbilt, son of the famous financier and transportation magnet, it was the brainchild of Horace R. Grant. Designed by some of Hartford’s best architects in the 1920s, the neighborhood still reflects the advantages that “modern living” offered Hartford’s elite.

By the 1920s and 30s the impact of the automobile was felt in West Hartford as the town became more accessible to Hartford’s middle and working classes. Between 1910 and 1930 the population of West Hartford grew from 4,808 to 24,941 residents. Then with the end of the Great Depression, World War II, and the exodus from urban centers, West Hartford witnessed a tremendous influx of people as its population swelled from 33,776 in 1940 to 62,382 people by 1960. This era ushered in major housing developments and retail spaces throughout the community.

In the 1960s, construction began on Interstate 84 and was completed in 1969. The interstate had many ramifications on the community. The most visible was that it bisected the town –isolating the more industrial and ethnically diverse neighborhood of Elmwood with a physical barrier from the rest of West Hartford. It also allowed for increased accessibility as the population increased with the Baby Boom and development. In the 1960s and 70s a variety of stores began to crop up in the Corbin’s Corner section of town (adjacent to I-84) and in 1974 Westfarms Mall opened. The viability of the mall would not have been possible without access to the interstate and the flood of people driving on it. The interstate recalibrated the traditional retail sites. Bishops Corner on the north end which had exploded with development in the early 1950s and 60s with such stores as Lord & Taylor, F.W. Woolworth, and Doubleday Book Shop and the Center with its largely independently owned stores were negatively impacted by the new retail traffic patterns.

West Hartford Today

Today, West Hartford epitomizes much of modern America. Walk through the town’s many neighborhoods and you will experience a range of architectural styles that document the development of the community and the people who have called it home. On commercial streets such as North and South Main Street or New Britain and Farmington Avenue store fronts not only documents the town’s evolving industries, but also its growing diversity with Asian markets, Kosher Bakeries, and a smorgasbord of ethnic restaurants.

In its journey from colonial parish, to suburb, to small city, West Hartford has undergone significant changes. Its story represents American’s shifting life styles, the growing diversity brought about by immigration, and the ever altering way we define home and place.