Noah Webster’s Story

Adapted from a lecture by Dr. Freeman Meyer, October 1987

The Noah Webster House in West Hartford is the birthplace of one of the most unappreciated men in American history. Our great military heroes and statesmen we remember. Even our writers if they write novels. But an author of a speller? A dictionary? Noah Webster belongs in the American Hall of Fame.

Webster’s life span of some [84] years is intensely interesting. Webster was sometimes pompous, often just plain pig-headed and stubborn; he grew increasingly conservative in both politics and religion. He was a complex man, with both virtues and vices. But one virtue he had above all others: a love of country, which was apparent throughout the entire 65 years of his adult life.

Noah’s Family

Noah Webster’s ancestors migrated to America in the seventeenth century. The name Webster, English in origin, means female weaver. There is a lot of confusion between Noah and Daniel Webster, but there was no relationship between them. Daniel Webster is best known as a lawyer, a member of Congress, a secretary of state, and perhaps the greatest orator of the first half of the nineteenth century. Noah Webster’s fame is quite different: it rests on his pen.

Noah Webster was in the sixth generation of his family in America. Noah Webster, Senior, Noah’s father, was born in Hartford in 1722 and settled early in what was then called the West Division of Hartford (now known as West Hartford), and he lived to the ripe old age of 91. He held many posts in the local government and married Mercy Steele in 1749. She was a descendent of Governor William Bradford of Massachusetts, so Noah Webster, Jr. had a distinguished background with two governors in his past. Noah and Mercy Webster had five children: Mercy, Abraham, Jerusha, Noah and Charles. Longevity was common in this family. The five children lived until the ages of 70, 80, 70, 85 and 55, an average life span of 72 years.

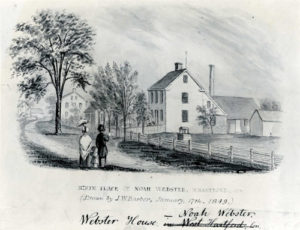

The Noah Webster House on South Main Street

We don’t know who built the house, or exactly when, but it was probably built by Noah, Senior. It was part of a farm of about 90 acres. At the time of Noah Junior’s birth, the house had only four rooms. The lean-to addition was added in 1787 and in the nineteenth century, a series of ells were built. An ell used to be where the changing exhibit gallery is now.

Noah Webster, Sr. sold the house to the Hurlburts in 1790. They held it through the nineteenth century. In 1899 they sold it to the Tilletsons, and they sold it to the Hamiltons in 1909. The Hamiltons were the last ones to live in the house. Fred, who was a member of the Noah Webster Board of Trustees, remembers looking out back and being able to see right to Ridgewood Road. Only pasture lay between this house and that road. The Hamiltons gave the house to the town in 1962, and at that point the house literally began to die, and continued to deteriorate until the Noah Webster Foundation formed in 1965 and began restoring the house.

This is a modest four-room center chimney house that Webster lived in, two above and two below. In 1763 eight people lived in the house. This included Noah, Sr. and his wife Mercy, their five children Mercy 14, Abraham 12, Jerusha 7, Noah 5, Charles 1 and Grandmother Steele. Family meant a lot to people of that period, and they lived very close together.

Noah’s Schooling

We know little about Noah’s early life. He probably began school at the age of seven, which was typical. This schooling would continue as long as the father would permit it. For most common people, boys were expected to work full-time on the farm at the age of about 10 or 11. When Noah reached the age of 14, in 1772, we have the first recorded evidence of his scholarly potential. In the eighteenth century the best educated man in a community would be the Congregational minister, who had usually gone to Yale or Harvard. He frequently used his knowledge to train boys who might aspire to attend college. Such a minister was the Reverend Nathan Perkins, minister of the West Division’s Congregational Church. (Perkins went to what is now Princeton). We don’t know whether Perkins found Webster or if Webster applied to Perkins, but they found each other. Webster requested that the pastor help him in preparing for entrance to Yale. From the moment that Webster began to learn Latin (and you couldn’t be educated without knowing Latin), he was a scholar. He was taken to books; he loved to read and exhibited this throughout the rest of his life. Noah was the only one in his family who went beyond a grammar school education.

After two years of tutoring by Perkins, at the age of 16, Noah went off to Yale. Sixteen was the typical college entrance age at that time. Noah started college at an exciting time in 1774. The Boston Tea Party had just occurred, the Coercive Acts had been passed and it was clear that we were headed toward a war. Before he was well into his first classes, the shots heard round the world had been fired at Lexington.

Webster’s class of 1778 was a very distinguished one, with Noah himself, Joel Barlow and Oliver Wolcott. Nathan Hale was a senior when Noah’s class entered Yale.

On June 15, 1775 the Continental Congress appointed George Washington Commander in Chief of the American Army, which was laying siege to Boston. He was sent up to Boston to take command, and as he passed through New Haven, Webster got his first glimpse of Washington. Webster later boasted that the Yale students serenaded the Commander in Chief, and Noah played the flute.

Noah Webster did not see active duty during the war. The one chance he had was the Battle of Saratoga in 1777. General Burgoyne was surrounded by American troops; the call went to New England that he was trapped, and that New England should send all of the men that they could. Webster, his two brothers and his father set out for Saratoga to join that battle, but as they were approaching, they got the word that Burgoyne had been taken and that the Americans had captured about 5,000 redcoats.

Webster graduated from Yale in 1778 and decided to take up the law. This was a very controversial time in his life. According to his diary, he went to his father to ask for financial assistance, and his father, in effect, turned him down. He gave him some worthless Continental Currency and said, “This is all I can do for you; I can do no more.” Then Noah went to his room for several days to try to figure this thing out.

Noah the Married Man

Noah Webster married Rebecca Greenleaf of Boston, whom he always called Becca. His diary offers a running account of his romance with Becca in the spring of 1787. They had a normal two year courtship and were married in 1789. They spent Thanksgiving of that year at this house, and that may well have been their last visit to Noah’s birthplace, since Noah Senior sold the house in 1790.

Romantic letters from Noah to Rebecca, attesting to their loving relationship, are part of the historical collections at the Noah Webster House, as well as the Webster ring. The center of this ring contains hair, believed to be that of Noah and Rebecca. On the back an inscription reads:

Noah Webster

Rebecca Webster

Noah the Teacher

Since he could not go into law immediately, Webster went into teaching. He possibly taught first in Glastonbury and then taught in Hartford for a while and lived with Oliver Ellsworth, one of the state’s most distinguished jurists. In those days most potential lawyers did not go to law school. Instead they “read law,” residing with a lawyer and learning from him, his books and records. Webster did this with Ellsworth.

In 1779-1780, he taught in the West Division and lived in this house. During that winter, we get the first glimpse of the Noah Webster to be. Elementary education was in a deplorable state. The one room school house was a very poor system of education. The school houses were usually ill-heated, ill-lit, the textbooks were poorly written and scarce, the teachers were ill-paid, and the guiding rule of the school house was “spare the rod and spoil the child.” A class might have 50-70 students aged 6-16.

Most teachers were discouraged by the situation and so was Webster, but unlike most others, he sat down and wrote an essay. Throughout his life, whenever he saw something that he felt needed correction, he wrote something about it in the form of an essay. He saw this as a challenge. Webster felt that Americans should have their own text books, and that they should not rely on English textbooks. He also felt that Americans should have copyright laws to protect authors. He believed that Americans should have their own dictionary. Webster wrote, “People never misapply their economy so much as when they make mean provisions for the education of children.” He went on to say that teachers should spare the rod and encourage students to learn. “The pupil should have nothing to discourage him.”

He continued to study law, passed the bar in 1781 and returned to teaching, this time in Sharon, CT and later in Goshen, NY. He started to draft the “Blue-Backed Speller” and completed it in 1783. After he published the “Blue-Backed Speller,” he opened a law office in Hartford but spent most of his time petitioning legislatures for adoption of copyright law and promoting the “Speller.”

Noah’s Writings and Publications

The “Blue-Backed Speller”

Spellers were text books that taught students how to read, spell and pronounce words. Most educators believed that children did not need to understand what they were reading, so teaching was done using recitation and memorization. Most spellers used in America were from England and taught English pronunciations, geography and historical facts. Now that America had won its political independence, it now needed to win its cultural independence. Noah thought that Americans needed their own speller that would teach American ways and instill a sense of pride in the new nation. He scoffed at English textbooks which did not contain words that were purely American or American geography.

First published in 1783, Webster planned to call his “Speller” the American Instructor, but the president of Yale, Ezra Stiles, suggested a more grandiose title. Webster adopted it: A Grammatical Institute of the English Language. In the book Noah implemented changes that helped to improve the teaching of pronunciation, spelling and reading. The “Speller” was used all over the country and therefore helped to standardize pronunciation in America. As a result, our country is most homogeneous in terms of spelling and pronunciation.

To promote the “Speller,” Noah systematically traveled from state to state, meeting with politicians and war heroes, asking each to attest to the greatness of his book. He would ask each to introduce him to someone else, thereby getting introduced to all the important people of that time. His used this huge list to influence the publisher to take on his project.

Throughout its history, between 50,000,000 and 100,000,000 copies were sold (though Noah never made much money on it). The speller was the number one used school book in America until the end of the 19th center when it was gradually replaced by the McGuffy reader.

The Dictionary

Noah realized that England and the new United States had different forms of government, institutions, customs and laws. Because of this, he believed that they needed different vocabularies. He also knew that science and technology were developing rapidly, and new words were being introduced just as quickly. So, he spent over 25 years researching words and their origins and writing the first American dictionary. This dictionary helped Americans to feel pride in their new country, and enabled everyone across the new nation to have a standard vocabulary.

Webster’s greatest achievement was the dictionary. In 1800 he published his intentions of writing a dictionary. He published a shortened, concise but comprehensive, version in 1806. The final version was finished in 1825 and published in 1828. It contained 70,000 words. It is no exaggeration to say that it was immediately accepted as the greatest dictionary of the English language on both sides of the Atlantic. Webster had an absolute genius for defining words.

Dining with President Andrew Jackson in the White House

When he was ready to publish the book, he found that there were no federal copyright laws. Any one could make copies, and he would get no income from it. This was because the Federation Government that existed then did not have the power to pass a copyright law. Therefore, if he wanted protection of his books, Webster would have to go to every state and get every state legislature to grant him a copyright. Under the new Constitution of 1789, that was changed, partially as a result of Webster’s work. In 1790 our congress passed the first federal copyright law, which granted 14 years of protection.

Webster continued to work for better copyright legislation for the rest of his life. His efforts were rewarded in the 1830-1831 congressional session, when congress seemed ready to improve the law. Webster was a distinguished man of letters, and people listened to him. He received three honors in Washington: he was allowed to address Congress in person on the copyright question, he was invited to dine at the White House with President Andrew Jackson, and he watched as the new bill was passed into law. The new law granted protection of the author or his heirs for 28 years, with the right of renewal for another 14 years.

Webster described his dinner at the White House in uncomplimentary ways. “The president asked me to dine with him and I could not well avoid it. We sat down at 6:00 and rose at 8:00. The president was very sociable and placed me, as a stranger, at his right hand. The party, mostly members of the two houses, consisted of about 30. The table was garnished with artificial flowers placed in gilt urns, supported by female figures on gilt waiters. We had a great variety of dishes, French and Italian cooking. I do not know the names of one of them. I wonder at our great men who introduce foreign customs to the great annoyance of American guests. To avoid annoyance as much as possible, the practice is to dine at home and go to the president’s to see and be seen, to talk and to nibble fruit and to drink very good wine. As to dining at the president’s table, in the true sense of the word, there is no such thing.”

Meeting George Washington

Webster felt that the American central government, the Articles of Confederation, was too weak. He found with his copyright experiences that a weak central government, granted few powers by the states, was dangerous. In his 1785 publication, Sketches of American Policy, Webster tried to convince people to call another convention to draft an amended form of the confederation, or a new plan of government. Webster showed the sketches to George Washington at Mount Vernon, and Washington showed them to James Madison. So clearly, the Sketches had something to do with the calling of the convention and the framing of the constitution.

A Founder of Amherst College

In 1808, Noah had a religious conversion experience. His wife and children brought him to an evangelistic meeting. He was “saved” and this had a profound affect on his thinking in a lot of areas. He became much more conservative as a result of this experience. In 1812 he moved from New Haven to Amherst, Massachusetts and helped to found Amherst College.

A Man of Varied Predictability

As successful as Noah Webster was, he had notable weaknesses. He was arrogant. When he went to Philadelphia for the first time Dr. Benjamin Rush met him and said, “I congratulate you on your arrival at Philadelphia,” to which Webster replied, “Sir, you may congratulate Philadelphia on the occasion.”

He was against the Bill of Rights, as were many people. He felt that freedom of the press would be abused. He argued that women should be educated enough to raise children, but no further. They should never go above their station and should never read novels. He felt that female education should be in support of the husband, the family and caring for the house.

In the early nineteenth century, he stated that no one should vote until he turned 45 and that no one should hold office until the age of 50. He was 50 at the time. He supported the church tax in Connecticut, while most opposed it. He also supported the Anti-War of 1812 Hartford Convention. He translated the Bible because he thought it was dirty and felt that “a woman couldn’t read it without blushing.”

While he was often thought of as “stiff” and a “curmudgeon”, he also had a fun-loving side. In his younger years he would socialize and “paint the town Red” with his friend, Benjamin Franklin. He was known to love music and dancing and was a very committed family man.